14. Equalizing Difference Model#

14.1. Overview#

This lecture presents a model of the college-high-school wage gap in which the “time to build” a college graduate plays a key role.

Milton Friedman invented the model to study whether differences in earnings of US dentists and doctors were outcomes of competitive labor markets or whether they reflected entry barriers imposed by governments working in conjunction with doctors’ professional organizations.

Chapter 4 of Jennifer Burns [Burns, 2023] describes Milton Friedman’s joint work with Simon Kuznets that eventually led to the publication of [Kuznets and Friedman, 1939] and [Friedman and Kuznets, 1945].

To map Friedman’s application into our model, think of our high school students as Friedman’s dentists and our college graduates as Friedman’s doctors.

Our presentation is “incomplete” in the sense that it is based on a single equation that would be part of set equilibrium conditions of a more fully articulated model.

This ‘‘equalizing difference’’ equation determines a college-high-school wage ratio that equalizes present values of a high school educated worker and a college educated worker.

The idea is that lifetime earnings somehow adjust to make a new high school worker indifferent between going to college and not going to college but instead going to work immediately.

(The job of the “other equations” in a more complete model would be to describe what adjusts to bring about this outcome.)

Our model is just one example of an “equalizing difference” theory of relative wage rates, a class of theories dating back at least to Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations [Smith, 2010].

For most of this lecture, the only mathematical tools that we’ll use are from linear algebra, in particular, matrix multiplication and matrix inversion.

However, near the end of the lecture, we’ll use calculus just in case readers want to see how computing partial derivatives could let us present some findings more concisely.

And doing that will let illustrate how good Python is at doing calculus!

But if you don’t know calculus, our tools from linear algebra are certainly enough.

As usual, we’ll start by importing some Python modules.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from collections import namedtuple

from sympy import Symbol, Lambda, symbols

14.2. The indifference condition#

The key idea is that the entry level college wage premium has to adjust to make a representative worker indifferent between going to college and not going to college.

Let

We now compute present values that a new high school graduate earns if

he goes to work immediately and earns wages paid to someone without a college education

he goes to college for four years and after graduating earns wages paid to a college graduate

14.2.1. Present value of a high school educated worker#

If someone goes to work immediately after high school and works for the

where

The present value

14.2.2. Present value of a college-bound new high school graduate#

If someone goes to college for the four years

where

The present value

Assume that college tuition plus four years of room and board amount to

So net of monetary cost of college, the present value of attending college as of the first period after high school is

We now formulate a pure equalizing difference model of the initial college-high school wage gap

We suppose that

We start by noting that the pure equalizing difference model asserts that the college-high-school wage gap

or

This “indifference condition” is the heart of the model.

Solving equation (14.1) for the college wage premium

In a free college special case

Here the only cost of going to college is the forgone earnings from being a high school educated worker.

In that case,

In the next section we’ll write Python code to compute

14.3. Computations#

We can have some fun with examples that tweak various parameters,

prominently including

Now let’s write some Python code to compute

# Define the namedtuple for the equalizing difference model

EqDiffModel = namedtuple('EqDiffModel', 'R T γ_h γ_c w_h0 D')

def create_edm(R=1.05, # gross rate of return

T=40, # time horizon

γ_h=1.01, # high-school wage growth

γ_c=1.01, # college wage growth

w_h0=1, # initial wage (high school)

D=10, # cost for college

):

return EqDiffModel(R, T, γ_h, γ_c, w_h0, D)

def compute_gap(model):

R, T, γ_h, γ_c, w_h0, D = model

A_h = (1 - (γ_h/R)**(T+1)) / (1 - γ_h/R)

A_c = (1 - (γ_c/R)**(T-3)) / (1 - γ_c/R) * (γ_c/R)**4

ϕ = A_h / A_c + D / (w_h0 * A_c)

return ϕ

Using vectorization instead of loops, we build some functions to help do comparative statics .

For a given instance of the class, we want to recompute

Let’s do an example.

ex1 = create_edm()

gap1 = compute_gap(ex1)

gap1

1.8041412724969135

Let’s not charge for college and recompute

The initial college wage premium should go down.

# free college

ex2 = create_edm(D=0)

gap2 = compute_gap(ex2)

gap2

1.2204649517903732

Let us construct some graphs that show us how the initial college-high-school wage ratio

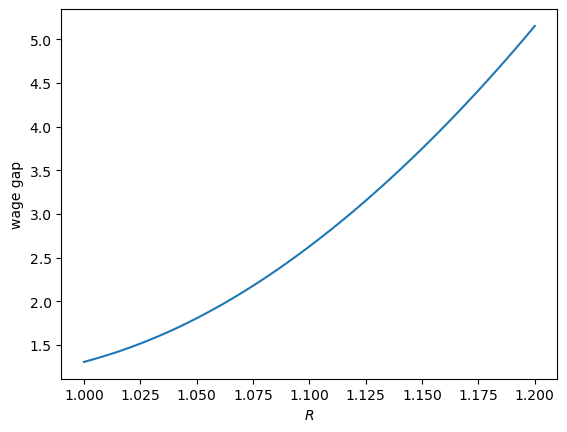

Let’s start with the gross interest rate

R_arr = np.linspace(1, 1.2, 50)

models = [create_edm(R=r) for r in R_arr]

gaps = [compute_gap(model) for model in models]

plt.plot(R_arr, gaps)

plt.xlabel(r'$R$')

plt.ylabel(r'wage gap')

plt.show()

Evidently, the initial wage ratio

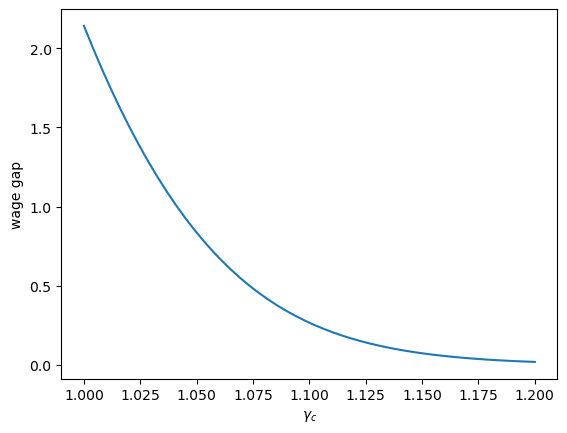

Not let’s study what happens to the initial wage ratio

γc_arr = np.linspace(1, 1.2, 50)

models = [create_edm(γ_c=γ_c) for γ_c in γc_arr]

gaps = [compute_gap(model) for model in models]

plt.plot(γc_arr, gaps)

plt.xlabel(r'$\gamma_c$')

plt.ylabel(r'wage gap')

plt.show()

Notice how the initial wage gap falls when the rate of growth

The wage gap falls to “equalize” the present values of the two types of career, one as a high school worker, the other as a college worker.

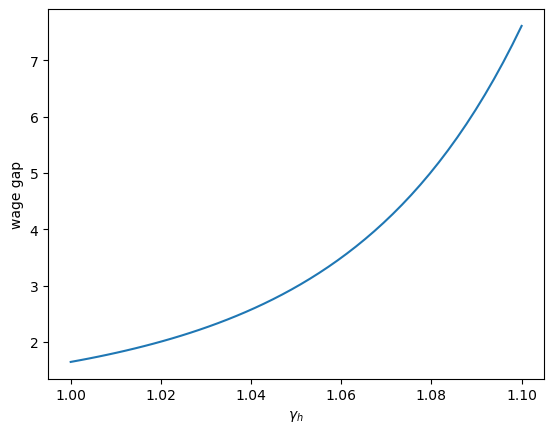

Can you guess what happens to the initial wage ratio

The following graph shows what happens.

14.4. Entrepreneur-worker interpretation#

We can add a parameter and reinterpret variables to get a model of entrepreneurs versus workers.

We now let

We define the present value of an entrepreneur to be

where

For our model of workers and firms, we’ll interpret

This cost might include costs of hiring workers, office space, and lawyers.

What we used to call the college, high school wage gap

We’ll find that as

Now let’s adopt the entrepreneur-worker interpretation of our model

# Define a model of entrepreneur-worker interpretation

EqDiffModel = namedtuple('EqDiffModel', 'R T γ_h γ_c w_h0 D π')

def create_edm_π(R=1.05, # gross rate of return

T=40, # time horizon

γ_h=1.01, # high-school wage growth

γ_c=1.01, # college wage growth

w_h0=1, # initial wage (high school)

D=10, # cost for college

π=0 # chance of business success

):

return EqDiffModel(R, T, γ_h, γ_c, w_h0, D, π)

def compute_gap(model):

R, T, γ_h, γ_c, w_h0, D, π = model

A_h = (1 - (γ_h/R)**(T+1)) / (1 - γ_h/R)

A_c = (1 - (γ_c/R)**(T-3)) / (1 - γ_c/R) * (γ_c/R)**4

# Incorprate chance of success

A_c = π * A_c

ϕ = A_h / A_c + D / (w_h0 * A_c)

return ϕ

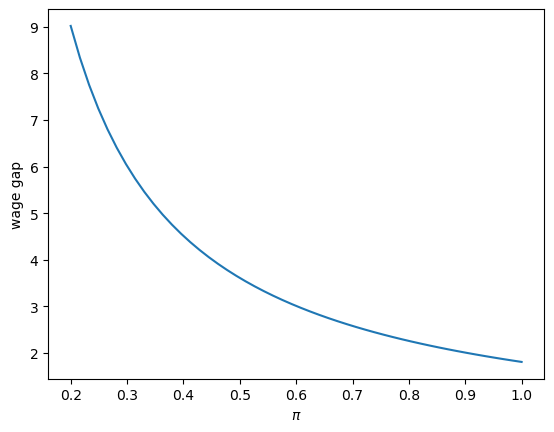

If the probability that a new business succeeds is

ex3 = create_edm_π(π=0.2)

gap3 = compute_gap(ex3)

gap3

9.020706362484567

Now let’s study how the initial wage premium for successful entrepreneurs depend on the success probability.

π_arr = np.linspace(0.2, 1, 50)

models = [create_edm_π(π=π) for π in π_arr]

gaps = [compute_gap(model) for model in models]

plt.plot(π_arr, gaps)

plt.ylabel(r'wage gap')

plt.xlabel(r'$\pi$')

plt.show()

Does the graph make sense to you?

14.5. An application of calculus#

So far, we have used only linear algebra and it has been a good enough tool for us to figure out how our model works.

However, someone who knows calculus might want us just to take partial derivatives.

We’ll do that now.

A reader who doesn’t know calculus could read no further and feel confident that applying linear algebra has taught us the main properties of the model.

But for a reader interested in how we can get Python to do all the hard work involved in computing partial derivatives, we’ll say a few things about that now.

We’ll use the Python module ‘sympy’ to compute partial derivatives of

Define symbols

γ_h, γ_c, w_h0, D = symbols(r'\gamma_h, \gamma_c, w_0^h, D', real=True)

R, T = Symbol('R', real=True), Symbol('T', integer=True)

Define function

A_h = Lambda((γ_h, R, T), (1 - (γ_h/R)**(T+1)) / (1 - γ_h/R))

A_h

Define function

A_c = Lambda((γ_c, R, T), (1 - (γ_c/R)**(T-3)) / (1 - γ_c/R) * (γ_c/R)**4)

A_c

Now, define

ϕ = Lambda((D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0), A_h(γ_h, R, T)/A_c(γ_c, R, T) + D/(w_h0*A_c(γ_c, R, T)))

ϕ

We begin by setting default parameter values.

R_value = 1.05

T_value = 40

γ_h_value, γ_c_value = 1.01, 1.01

w_h0_value = 1

D_value = 10

Now let’s compute

ϕ_D = ϕ(D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0).diff(D)

ϕ_D

# Numerical value at default parameters

ϕ_D_func = Lambda((D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0), ϕ_D)

ϕ_D_func(D_value, γ_h_value, γ_c_value, R_value, T_value, w_h0_value)

Thus, as with our earlier graph, we find that raising

Compute

ϕ_T = ϕ(D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0).diff(T)

ϕ_T

# Numerical value at default parameters

ϕ_T_func = Lambda((D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0), ϕ_T)

ϕ_T_func(D_value, γ_h_value, γ_c_value, R_value, T_value, w_h0_value)

We find that raising

This is because college graduates now have longer career lengths to “pay off” the time and other costs they paid to go to college

Let’s compute

ϕ_γ_h = ϕ(D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0).diff(γ_h)

ϕ_γ_h

# Numerical value at default parameters

ϕ_γ_h_func = Lambda((D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0), ϕ_γ_h)

ϕ_γ_h_func(D_value, γ_h_value, γ_c_value, R_value, T_value, w_h0_value)

We find that raising

Compute

ϕ_γ_c = ϕ(D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0).diff(γ_c)

ϕ_γ_c

# Numerical value at default parameters

ϕ_γ_c_func = Lambda((D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0), ϕ_γ_c)

ϕ_γ_c_func(D_value, γ_h_value, γ_c_value, R_value, T_value, w_h0_value)

We find that raising

Let’s compute

ϕ_R = ϕ(D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0).diff(R)

ϕ_R

# Numerical value at default parameters

ϕ_R_func = Lambda((D, γ_h, γ_c, R, T, w_h0), ϕ_R)

ϕ_R_func(D_value, γ_h_value, γ_c_value, R_value, T_value, w_h0_value)

We find that raising the gross interest rate